2007-10-31

grappling with truth

I understand the argument that the scientist aims not to make a claim of truth, but rather, is making a thesis that aims to explain as best as possible a set of observations. This thesis in turn is subject to a counter thesis that in fruition forms a new thesis, and so on. As Marko said in class this new thesis is “better” (I suppose because it is successful not only on its own but also in encompassing the thesis that precedes it).

Here is where it gets complicated for me. If, and again I’ll quote Marko, the new thesis is “better” then is it not in that regard higher on the linear continued of knowledge? Is it not more truthful? Even if ‘the scientist’ is ultimately reluctant to say that the ‘heavens’ are attainable, that is that absolute truth is the goal, don’t these types of pursuits still necessitate the notion of there being a truth? The fact that scientists do not make statements of truth does mean that their work operates independent of a belief in it –celestial as it may be. [Perhaps this is where I need Jonathan M to compose a visual diagram]. So, am I disagreeing, enforcing or just completely missing your point Marko?

As someone who’s background is in sociology, I am not simply interested in vilifying the natural sciences; In terms of ‘the social sciences’ the notion of progress is crucial. Last night Judith Butler gave a public lecture and said that having a critical stance towards the notion of progress does not mean that you deny that some types of progress exists or even that some types of progress are good. Can we deny the benefits to human health that have come from scientific discoveries (or is that scientific theses??) or, for that matter, the benefits that come from the intellectual struggles for human liberties? [Wow, those questions are cliché!].

In anticipation of our final class in which we are meant to produce something, this is what I’m thinking about when contemplating the idea of trying to contribute to a meaningful conclusion to the class.

I’ll give the last words to Judith Butler who brought her essay to a close by quoting Nietzsche who quipped in The Will to Power “'Mankind' does not advance, it does not even exist."

2007-10-30

If you go into the woods today...

Menacing-verdant too good to be true landscape plays an enormous part in Stalker. When Jackie was talking about that village in Dorset she mentioned that you "don't stray from the path", and this seemed to beautifully reference the film - all the terror engendered by the idea of the Writer going directly to the room without following the painful way round, the constant repetitions of "you don't do that here", "this is where you go", "this is how things work here". It's not just reverence, it's fear; if you stray from the path something terrible will happen. The Zone has its own internal logic and its own rules and woe betide those who try to fault them. It's as though the film is tapping into an earlier subconscious Russian narrative, the heavily wooded folk tales of Vladimir Propp, the kind of stories that gave birth to, say, Angela Carter; an older threat than the (possibly) nuclear one suggested by the film, but somehow similar, a faceless danger in the woods that will either kill you (if you don't behave) or cure you (if you do).

On those relentlessly hot July afternoons, Ada liked to sit on a cool piano stool of ivoried wood at a white-oilcloth'd table in the sunny music room, her favourite botanical atlas open before her, and copy out in colour on creamy paper some singular flower. She might choose, for instance, an insect-mimicking orchid which she would proceed to enlarge with remarkable skill. Or else she combined one species with another (unrecorded but possible), introducing odd little changes and twists that seemed almost morbid in so young a girl so nakedly dressed. The long beam slanting in from the french window glowed in the faceted tumbler, in the tinted water, and on the tin of the paintbox - and while she delicately painted an eyespot or the lobes of a lip, rapturous concentration caused the tip of her tongue to curl at the corner of her mouth, and as the sun looked on, the fantastic black-blue-brown-haired child seemed in her turn to mimic the mirror-of-Venus bloom.

Ada also, Hesse-Honiger-like, has a 'larvarium' full of insects, which serve via their (often mutating and deliberately mispronounced) names, like the Wolf Man's multi-lingual butterfly, as hot-beds of enmeshing or encryption.

fleas

The Flea

by John Donne

Mark but this flea, and mark in this,

How little that which thou deniest me is;

Me it sucked first, and now sucks thee,

And in this flea our two bloods mingled be;

Thou know’st that this cannot be said

A sin, or shame, or loss of maidenhead,

Yet this enjoys before it woo,

And pampered swells with one blood made of two,

And this, alas, is more than we would do.

Oh stay, three lives in one flea spare,

Where we almost, nay more than married are.

This flea is you and I, and this

Our mariage bed and mariage temple is;

Though parents grudge, and you, we are met,

And cloisterd in these living walls of jet.

Though use make you apt to kill me,

Let not to that, self-murder added be,

And sacrilege, three sins in killing three.

Cruel and sudden, hast thou since

Purpled thy nail in blood of innocence?

Wherein could this flea guilty be,

Except in that drop which it sucked from thee?

Yet thou triumph’st, and say'st that thou

Find’st not thy self, nor me the weaker now;

’Tis true; then learn how false, fears be:

Just so much honor, when thou yield’st to me,

Will waste, as this flea’s death took life from thee.

You've watched the movie...

Here's a link to the wikipeida entry of the game Marko mentioned below. It's gives a much more concise overview of the game than the official website.

2007-10-29

Pripyat and Chernobyl

While much of the photography of Chernobyl follows predictable patterns of aftermath aesthetics (a single abandoned plimsoll or weeds sprouting in cracked buildings), the circle of references was neatly completed in 2007 when a Ukrainian company made an FPS computer game called S.T.A.L.K.E.R. Shadow of Chernobyl, using digitised photos of the zone.

mark aerial waller interview

http://www.necronauts.org/interviews_mark.htm

2007-10-24

Nowfroth Report 03

01: Burn, Hollywood, Burn - (callous, I know) a link to the CNN California Wildfires page

01(extra): 'Devil Wind' Stokes Flames

01(more): Interactive Google Wildfires Map

02: A visit to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park

03: Odd behaviour of birds at Chernobyl (strictly for those with ornithological interests)

04: Never saw this one coming: have a look at Wikipedia's entry on Titanic: The Musical

2007-10-23

It went without saying . . .

2007-10-22

Mind Maps: Number 3 at Sea

You've seen the film, heard the song, now play the game...

You've seen the film, heard the song, now play the game...The Year is 1912.

For 2-6 players ages 7 and up.

“We will remember you. I hope you will remember us.”

This sets up an interesting question about the relationship between catastrophes – clearly the way in which the events of 1973 have been interpreted has changed significantly since 2001. While Loach’s film won the prize for best short at the Venice film festival, Alexander Walker in the Evening Standard claimed it was “as disreputable an act as setting up your Marxist stall on the graves of 2,800 victims. His mini-film brings shame on our country."

Richard

2007-10-21

Collect them all!!

2007-10-19

Chen Chieh-jen

The mashup trailer for Titanic 2 was made by Robert Blankeneim and I agree with the comment that the mashup process is itself quite oneiric in that it takes, say, Leonardo di Caprio's entire body of work almost as if it were the day residue for the production of the dream/mashup.

As a fine example of Youtube culture, Titanic 2 combines the tradition of the mashup, as for example in Christian Marclay's Up and Out, with that of the fake trailer, as for example in Francesco Vezzoli's Trailer for a Remake of Gore Vidal's Caligula (2005).

Absalom! Absalom!

‘Maybe we are both Father. Maybe nothing ever happens once and is finished. Maybe happen is never once but like ripples maybe on water after the pebble sinks, the ripples moving on, spreading, the pool attached by a narrow umbilical water-cord to the next pool which the first pool feeds, has fed, did feed, let this second pool contain a different temperature of water, a different molecularity of having seen, felt, remembered, reflect in a different tone the infinite unchanging sky, it doesn’t matter: that pebble’s watery echo whose fall it did not even see moves across its surface too at the original ripple-space, to the old ineradicable rhythm thinking Yes, we are both Father. Or maybe Father and I are both Shreve, maybe it took Father and me both to make Shreve or Shreve and me both to make Father or maybe Thomas Sutpen to make all of us.’

Needless to say, the back-story turns out to involve incest.

2007-10-17

A historiography - Roger talks to Machiko

M: We are victims . . . always victims. We know a bomb dropped and many people died. And there's Leukaemia.

R: That's in school? You learn this in school?

M: Yes. And there are pictures of people in the river - burning people.

R: Is there any blaming?

M: What?

R: Do you blame anyone?

M: War is to blame.

R: And America?

M: We don't hear that. No-one says anything about that.

R: Just war.

M: War.

(Machiko is a Japanese artist whose parents were not alive in 1945; her grand parents were however. Neither have said anything to her about the A-bomb blasts in Hiroshima or Nagasaki. The topic is taught in all schools in Japan.)

2007-10-16

The Painting of Modern Life

http://www.haywardgallery.org.uk/. It features the likes of Warhol, Richter and Hockney exploring the relationship between photography and painting, and the first couple of rooms are particularly relevant to this course – with images of car crashes, race riots, explosions … and the Queen Mum’s funeral. The explanatory blurb also contains this revealing quote from Marlene Dumas: “Everything everyone holds against painting is true. It is an anachronism. It is outdated. It is obscene the way it turns any kind of horror into a type of beauty. Why do we still care to look at images? That’s why I continue to create them.”

Richard

Nowfroth Report 02

- Disaster tolls, democracy levels linked

- The future is not what is used to be ("An apocalypse is sadly attractive. If we cause catastrophe--by our rape of the planet, our failure to address a social problem or we anger a deity--then our generation becomes the most important to ever have lived.")

- Black Friday fishing disaster tributes unveiled

- 21 dead in Colombia mine disaster

- Training disaster kills nine soldiers

- Catastrophe at Rafah Crossing

2007-10-13

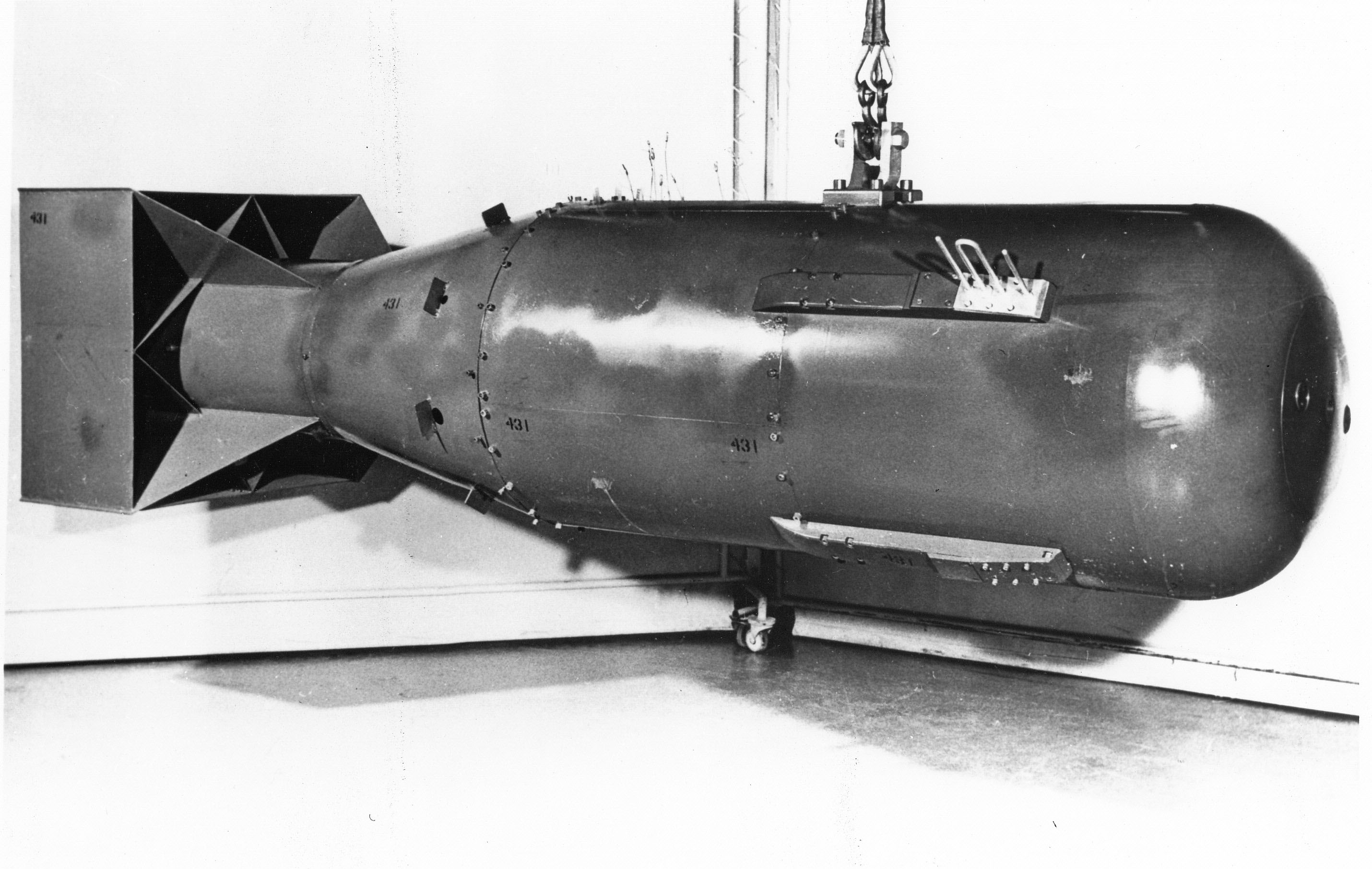

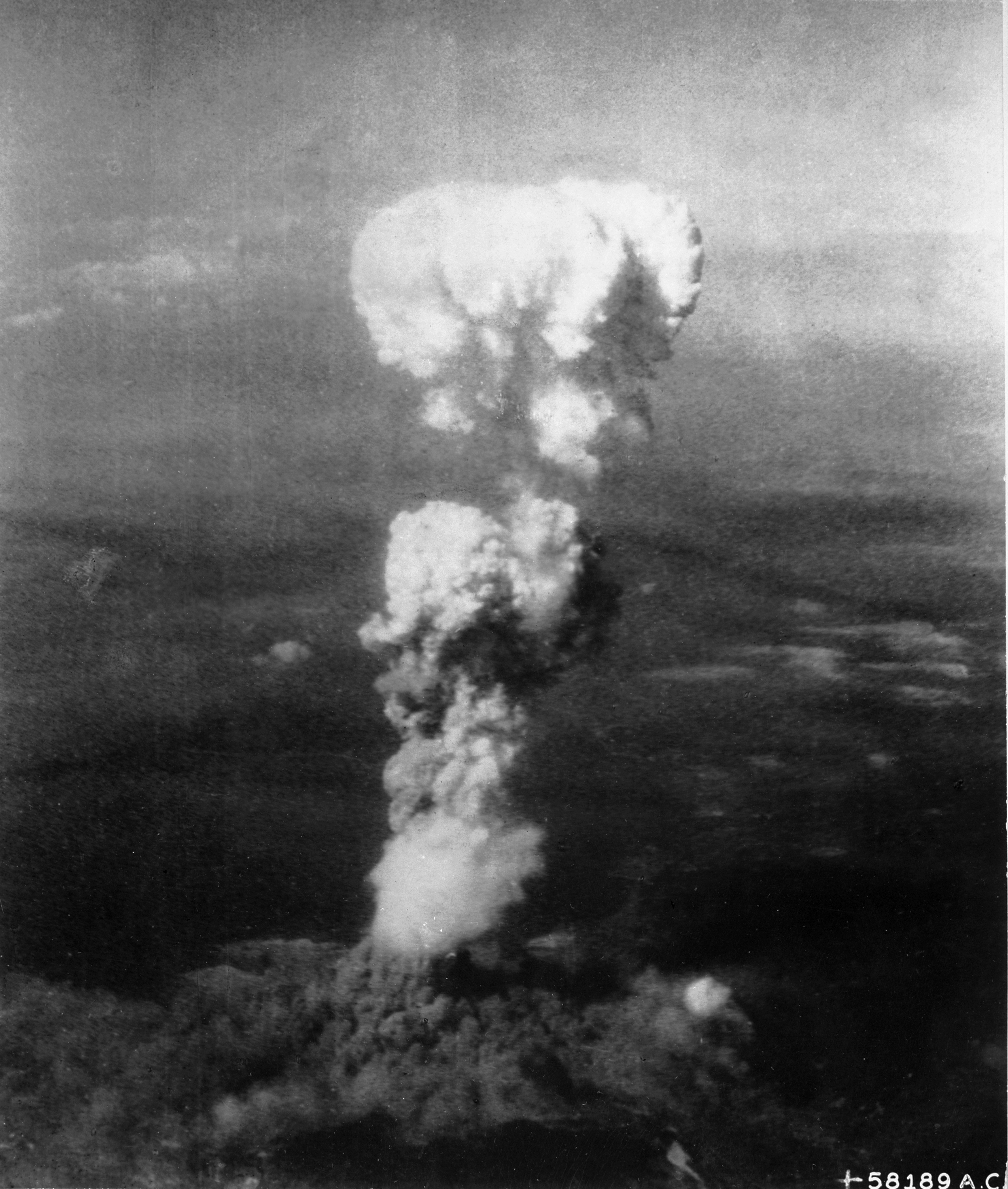

Images for session Two: August 6th, 1945

Photograph of a mock-up of the Little Boy nuclear weapon dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, in August 1945. This was the first photograph of the Little Boy bomb casing to ever be released by the U.S. government (it was declassified in 1960).

This image is a work of a United States Department of Energy (or predecessor organization) employee, taken or made during the course of an employee's official duties. As a work of the U.S. federal government, the image is in the public domain.

Source: http://www.chinfo.navy.mil/navpalib/images/historical/hiroshima.jpg License: All information on this site is considered public information and may be distributed or copied.

Burn razed field 1,200 meters south of the hypocenter seen from the roof of the Higashi Police Office, Hiroshima.

Looking the disastrous scene at the hypocenter of Nagasaki from the Hospital of the Nagasaki University of Medicine 700 meters south east of the center.

A person who sat on the step evaporated, only leaving the shadow.

Sours: http://www.geocities.jp/chikushijiro2002/peace1e.html

Map of Blast and Fire Damage to Hiroshima

Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Image:Hiroshima_Damage_Map.gif

This photographic image was published before December 31st 1956, or photographed before 1946 and not published for 10 years thereafter, under jurisdiction of the Government of Japan. Thus this photographic image is considered to be public domain according to article 23 of old copyright law of Japan and article 2 of supplemental provision of copyright law of Japan.

An atomic bombed victim had the injury dressed in the Hiroshima Hospital of the Japan Red Cross.

from original prints by Mr. Yoshito Matsushige

Copyright owner is "The Chugoku Shimbun", a regional newspaper.

Portrait of Yosuke Yamahata, photographer. (See http://www.peace-museum.org)

Portrait of Yosuke Yamahata, photographer. (See http://www.peace-museum.org)

Don’t forget Hiroshima and Nakasaki by Takanori Matsumoto

Also see:

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Hiroshima

http://www.exploratorium.edu/nagasaki/journey/journey1.html

2007-10-12

Mind Maps in Russell Square

baumann/landsmann

http://www.necronauts.org/interviews_simon.htm

Tom McC

some references, as promised

Charles Figley, Strangers at Home: Vietnam Veterans Since the War, 1980; Bessel Van der Kolk, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, Psychological and Biological Sequelae, 1984.

The Freud stuff:

'Beyond the Pleasure Principle', 1920

'A Note upon the "Mystic Writing Pad"', 1925

Also, Simon Critchley: 'The Original Traumatism', in 'Ethics-Politics-Subjectivity', 1995

The Derrida text:

Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, 1995

The other Ballard book:

The Atrocity Exhibition, 1970 (amazing book, very short)

The passage I alluded to from Burroughs:

Chapter entitled 'Pry Yourself Loose and Listen' in 'Nova Express', 1963

And finally, check out this remarkable (very short) story by Donal Barthelme called 'Game', in which two men sit in a nuclear bunker waiting for their relief, wondering whether they should kill one another and cradling each other to sleep as they sing Mozart. You can read it online here:

http://williamstallings.com/SS/Humor/Game.pdf

Best, Tom McC

2007-10-11

On Angels, Demons and Hobgoblins

http://usuarios.lycos.es/asocinnuendo/Grandville.jpg

I’m glad Alice mentioned Benjamin’s angel of history in an earlier post – this figure has been lingering in my mind as well, as it seems to connect with some of the most critical aspects of the course.

It is perhaps testament to the catastrophic character of the last century that, just nine years after his 1931 radio broadcast on the Lisbon earthquake, in which he optimistically identified the science of prediction with our eventual salvation from such tragedies, Benjamin would present such a comparatively doom-laden view of our historical destiny. In the years following 1931 the Nazi Party rose to power, and proceeded to perpetrate some of the twentieth century’s most terrible atrocities in the name of an irresistible force of progress. Consequently, from around 1932 onwards, Benjamin’s life itself arguably constituted a hopeless flight from catastrophe.

In response to our discussion last week, I was prompted to imagine a kind of demon accompanying the angel of history. Whilst the angel of history contemplates the past, perceiving in horror the ever rising tide of ruin it leaves behind, its demonic twin gazes in detached rapture at immediacy, the newness of the now, the now-froth, and so, blind to its destructive trail, surfs gleefully on the spectacle of history’s disintegration. I think that traces of this second figure can possibly even be found to haunt Benjamin’s earlier radio broadcast, particularly given the medium through which it was delivered. Far from refining our control over the future, it often seems that the most significant consequence of technological development has been a surplus of media, always interceding too late. Since the spread of pamphlets, which Benjamin describes, documenting purportedly eye-witness accounts, the scope, scale and intensity of the popular media has exploded, generating a tidal wave of its own, which, in surging forth, has left a legacy of devastation in its wake. The enlightenment ideal of freedom founded in rationality, that which was supposed to quell this tide of historical destruction and in its place build at least a secure road towards the future, if not utopia itself, has, from this perspective, served only to feed a demon obsessed with the fractured transience of the now.

How are we to distinguish our discourse on catastrophe from the nihilistic bent of these twin incarnations of time?

In place of an answer I want to introduce a third figure, this time from Joyce’s Ulysses. Preceded, appropriately enough, by the Newsboys’ announcement of a ‘Stop press edition’, as well as Stephen Dedalus musing ‘A time, times and half a time’, this character can be seen to stand for the point towards which both angel and demon are heading. Certainly in Joyce’s account that which is encountered once history and the present have done their work, a capricious satirical creature, delighting in the vacillations of chance, is not exactly what might be expected. Perhaps even more surprisingly, once the goblin has made its exit, it only takes a stuck needle on a gramaphone record to allow history to continue on its way:

[…]A hobgoblin in the image of Punch Costello, hipshot, crookbacked, hydrocephalic, prognathic with receding forehead and Ally Sloper nose, tumbles in somersaults through the gathering darkness.)

ALL

What?

THE HOBGOBLIN

(His jaws chattering, capers to and fro, goggling his eyes, squeaking, kangaroohopping with outstretched clutching arms, then all at once thrusts his lipless face through the fork of his thighs.) Il vient! C'est moi! L'homme qui rit! L'homme primigène! (He whirls round and round with dervish howls.) Sieurs et dames, faites vos jeux! (He crouches juggling. Tiny roulette planets fly from his hands.) Les jeux sont faits! (The planets rush together, uttering crepitant cracks.) Rien va plus! (The planets, buoyant balloons, sail swollen up and away. He springs off into vacuum.)

FLORRY

(Sinking into torpor, crosses herself secretly.) The end of

the world!

The Evolution of Catastrophe as a Mind Map: Or How we negotiated the fissures

by Sylvia Plath in The Colossus

Compelled by calamity's magnet

They loiter and stare as if the house

Burnt-out were theirs, or as if they thought

Some scandal might any minute ooze

From a smoke-choked closet into the light;

No deaths, no prodigious injuries

Glut these hunters after an old meat,

Blood-spoor of the austere trajedies.

Mother Medea in a green smock

Moves humbly as any housewife through

Her ruined apartments, taking stock

Of charred shoes, the sodden upholstery:

Cheated of the pyre and the rack,

The crowd sucks her last tear and turns away.

2007-10-10

body vs. dust | body as dust

Both in terms of practical dealings with ground zero (the 'stuff' on the boots of the workers becoming human ashes) and in terms of the production of memory (detritus being blessed by a chaplain then scooped into silver urns by gloved hands), we see what Yaeger calls a "transition from rubbish to transcendence" (188) where pollution becomes sacred.

The beautiful opening sections of Hiroshima Mon Amour -glistening bodies, passionately intertwined, dust falling, silver detritus on the skin - has something to do with this transcendence, though I'm not sure if the relationship here, between body and matter, is the same or just the opposite.

Although Hiroshima and Nagasaki could be described as catastrophes of vaporization, much of the social coping and cultural documentation after the events bring focus to the intact body (and relationships between bodies). Deformed perhaps, but enduring still, these are the survivors --e.g. Ken Domon's "The Marriage of A-Bomb Victims", 1957, In Living Hiroshima, an image that shows domestic happiness born of daily existence.

Hiroshima Mon Amour begins the same, bodies against the oblivion, two bodies closed against the dust and insisting on their fleshiness.

On the other hand, wIth 9/11, all distinction between body and dust is gone. "He became part of that building when it came down" a loved one says of her husband (190). The dust is at once sickening and sacred.

No matter the form transcendence takes, the first abstract images of this film seem to make explicit this uneasy relationship between body and dust, thrust out of normal meaning in the event of catastrophe.

Patricia Yaeger. "Rubble as Archive, or 9/11 as Dust, Debris and Bodily Vanishing". Trauma at Home: 9/11. Ed. Judith Greenberg. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. 2003.

2007-10-09

Bailey's Acts of God

To, perhaps slightly, reformulate Bailey’s argument here, one may begin with the questioning of the locus of catastrophe [thus linking it up to the question of its gender that had come up]: is the concept of catastrophe not necessarily intertwined with the idea of a monotheistic [and thereby to a certain extent ‘Western’, despite its trace back to Vedic doctrines and its link to other principles such as Shiva/Vishnu, etc] cosmic order – i.e. one in which Being is transcendent to the material world, external to its ‘acts’ (or, for example, in Orthodox theology the so called ‘energies’, in Spinoza’s universe the modifications of the substance, etc)? Is it not only through the inability to live [by affirming] becoming that a culture can come to obtain the concept of disaster?

And does not Voltaire’s incapability of sustaining Leibnizian ‘tout est bon’ theodicy in the face of the Lisbon earthquake not stem precisely from this inevitable paradoxical nature of the disaster, in which the sense of Being so immediately brought forth by the surge of becoming makes for this impossible necessity of Being as being perceivable only through its emanation into or expression through the material world of becoming?

2007-10-08

Earthquake

I've been itching to mention Doris Salcedo's new commission for the Unilever Series, Shibboleth (2007) inthe Turbine Hall at Tate Modern. The news embargo has just been lifted and it's going to start bubbling up everywhere soon. Here is a wonky mobile phone shot of the crack that runs right through the Turbine Hall, as if the outcome of an earthquake. Salcedo relates the work to tragedy and says "It represents borders, the experience of immigrants, the experience of segregation, the experience of racial hatred." Quote from BBC News, where there is also a photo of the other end of the crack, as it were. The Guardian also has a story and others are sure to follow. As part of the nowfroth, it's interesting that The Guardian was the first UK paper last year to let its online edition lead with stories before they appear in print. Others soon followed suit in the accelerating news game.

I've been itching to mention Doris Salcedo's new commission for the Unilever Series, Shibboleth (2007) inthe Turbine Hall at Tate Modern. The news embargo has just been lifted and it's going to start bubbling up everywhere soon. Here is a wonky mobile phone shot of the crack that runs right through the Turbine Hall, as if the outcome of an earthquake. Salcedo relates the work to tragedy and says "It represents borders, the experience of immigrants, the experience of segregation, the experience of racial hatred." Quote from BBC News, where there is also a photo of the other end of the crack, as it were. The Guardian also has a story and others are sure to follow. As part of the nowfroth, it's interesting that The Guardian was the first UK paper last year to let its online edition lead with stories before they appear in print. Others soon followed suit in the accelerating news game.

the catastrophe matrix + more

Whenever I tackle a new subject I always have this weird urge to quantify and compare. And that usually means I want to draw something or find a visual way to express information.

Here are two early experiments.

The first figure is the 'Catastrophe Matrix' where I've assigned positions to various catastrophes. The axes I chose were death toll and um, presence in the mind of modern man, or notoriety I suppose. Obviously by reducing a catastrophe to a point on a graph I'm guilty of an almost blasphemous reduction (especially when I'm using words like 'big' and 'small'), and the positions have been assigned very recklessly - but I think it's part of starting to grapple with the subject (for me anyway).

The positions of different catastrophes necessarily change over time, but the thing that strikes me is how little death toll has to do with how much an event is recognised as a catastrophe (working with the idea of a catastrophe in a very literal way). It's as if there has to be an element of spectacle for us to acknowledge a catastrophe has taken place: we have to see the plane crashing into the towers, we have to imagine the largest ship in the world split in two, we need to be told that 'cathedral spires shook like reeds in the wind.' There's a terrible aesthetic threshold that needs to be crossed before we're really interested or engaged. If we want to use the idea of catastrophe being a blind spot then we could argue that the greatest catastrophes (malaria for example, or even modernity if we want to broaden the scope of the argument) are the ones that are most invisible, that are closest to the blind spot. Maybe we can't reckon with the catastrophe until it has some sort of aesthetic dimension?

The second diagram visualizes catastrophes in history as a kind of earthquake tremor diagram, similar to what we had in class. The epicentre, or point zero, is the point at which all life ends, and the proximity to that point is determined by how close we came to extinction (as a percentage of total population).

Crisis response

Something that came up on Friday is that catastrophe is, possibly, marked out as such because of the human response to it – like the tree falling in the forest going unnoticed, or the cataclysm that wiped out the dinosaurs being generally referred to as a natural event in the planet’s history rather than an overarching tragedy.

Something that came up on Friday is that catastrophe is, possibly, marked out as such because of the human response to it – like the tree falling in the forest going unnoticed, or the cataclysm that wiped out the dinosaurs being generally referred to as a natural event in the planet’s history rather than an overarching tragedy. Marko mentioned the ‘I was there’ thing, the need to implant oneself in the disastrous situation, which links to ‘where were you’– see JFK for the obvious one – and the tendency, also mentioned on Friday, to narrow big stories down to smaller, digestible bites: how many Britons were killed in the Asian tsunami, what their individual stories were. Which again takes us back to what (I think) is one of Blanchot’s primary assertions – the disaster is the blind spot, the hole in the fabric, the thing that cannot exist in either space or time because its existing negates all other existence, and as such it cannot be seen or witnessed, it is always already past or always an immediate threat but never the now (whatever the now may think itself).

I was wondering what we come up with, then, culturally, to help us cover over that blind spot. We disassociate by watching rolling news or YouTube ‘porn’, turning the Real – if there is a real? – exhaustion of the disaster into a small and unthreatening series of images (like the painting we saw on Friday of ship in tidal wave, which reduces terrifying nature to aesthetic object and allows us to look at it, appreciate and turn away unscathed). If the blank spot at the nexus of catastrophe can be compared to the ultimate threat, that which must not be viewed, of castration, then like castration it must involve all flavours of distraction and displacement to help us avoid looking. The necessity of not knowing castration can implement trauma and pathology; does this effect repeat itself on more generic disaster?

As an example, there seems to be a knee-jerk humour response to catastrophe in British culture. After the July 2005 bomb attacks on the London transport system some strong-jawed types set up this website to make a point that London would not be cowed; within hours this had gone up to make the point that London would not take anything seriously, even suicide bombers. Or if you’re on Facebook take a look at this, it’s a mass piss-take of the ‘I survived’ thing that people do after disasters. Humour as defence, humour as response, distancing mechanism, social cohesion device even. We know this, and we know the heroically inflected and ‘inspirational’ response to 9/11 in New York; it would be interesting to examine the public responses to disasters in other countries, find out whether these two diametrically opposed reactions are specific to the west, how, perhaps, Buddhist Thailand’s response to the tsunami differed. (I realise that one can’t dissolve an entire country down to one point of view, or define an entire population by their passports or lack thereof; this is necessarily going to involve some inelegant generalisations. However I think they’d be justified to some extent if they provide an understanding of the media and governmental response to disaster, the public face, as these are often the crucial clues as to how a country sees itself, how its self image operates.)

Nowfroth Report 01

01: Catastrophe insurance, or the sheer excitement of extreme risk

02: Detention centres create 'psychiatric catastrophe': study

03: Disaster in eight seconds

Ruined apartment block serves as grim reminder of earthquake for Islamabad residents

04: Ready or not, 'disaster' happens

Four-day drill will put local residents on alert, agencies on learning curve

05: 'War on terror' has been a 'disaster': British think tank

06: China warns of catastrophe from Three Gorges Dam

07: Climate change disaster is upon us, warns UN

2007-10-07

more on catastrophe and history

Walter Benjamin's famous allegory of the angel of history is interesting in respect to the post on catastrophe and the narrative of history. In his 'Thesis on the Philosophy of History' he talks about a Klee painting, 'Angelus Novus' (on the right), which in Benjamin's description depicts an angel about to move away from something he is looking at intently. For Benjamin, this is the angel of history: 'Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet'. The angel wants to stay, make things whole, but a storm propels him into a future to which his back is turned. This storm, for Benjamin, is 'what we call progress'.(Illuminations, 1999 edn., p. 249) The phrase to 'break with the past' springs to mind; 'progress' as violence. Angels again, too, though Benjamin sees this one as looking catastrophe in the eye, as opposed to the averted eyes of the Clama image.

Walter Benjamin's famous allegory of the angel of history is interesting in respect to the post on catastrophe and the narrative of history. In his 'Thesis on the Philosophy of History' he talks about a Klee painting, 'Angelus Novus' (on the right), which in Benjamin's description depicts an angel about to move away from something he is looking at intently. For Benjamin, this is the angel of history: 'Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet'. The angel wants to stay, make things whole, but a storm propels him into a future to which his back is turned. This storm, for Benjamin, is 'what we call progress'.(Illuminations, 1999 edn., p. 249) The phrase to 'break with the past' springs to mind; 'progress' as violence. Angels again, too, though Benjamin sees this one as looking catastrophe in the eye, as opposed to the averted eyes of the Clama image. Benjamin also talks about the state of emergency being the rule rather than exception. It's our task to 'bring about a real state of emergency' (Illuminations, p. 248) to 'improve our position in the struggle against Facism'. How does this relate, if at all, to Naomi Klein's take on 'states' of shock?

AG

2007-10-06

00 Zero or Shaken not Stirred

Secondly, I have looked into Acts of God (a little more), in relation to insurance and legal systems. An Act of God can be defined as a natural catastrophe, an unusual event not caused by human intervention which could not have been prevented by reasonable care or foresight, for example a hurricane, flood, earthquake, violent volcanic eruption, even locust plagues. You can get insurance against Acts of God, such as flood insurance etc. There is even Acts of God holiday insurance.

It can refer to property and personal damage and contracts dealing with the delivery of goods or services, the idea being to protect parties from litigation over delays or failures due to circumstances beyond their control. Origins of the phrase can be traced back to religious texts and the term was subsequently appropriated by insurance companies in the early 19th century. Some insurance policies still use the phrase Act/s of God today, though it is being replaced increasingly by secular terminology or put into quotation marks. In the film, The Man Who Sued God, (Australia: 2001), the protagonist is faced by an insurance company’s non-payment due to an ‘Act of God’… So, he sues God in the form of his earthly representatives.

There is also Catastrophe Modelling (Cat Modelling) - whereby computers are used to make calculations to estimate losses that could be sustained due to a catastrophic event (in insurance) and Catastrophe Theory (Mathematics).

To take up on the idea that “perhaps modernity is catastrophic (with radical newness) because it is the age in which technology has developed such that it can destroy the earth (nuclear weaponry, global warming etc)”. The Catastrophe, Revolution and the Narrative of History post foregrounds technology as being inherently bad, given the examples. The effects of modernity are surely not all detrimental? For example, there has been a control or eradication of epidemics and disease, and improvements in communication, such as this blog etc. Modernity covers a wide spectrum.

power and disaster

Obviously there is often a lot of money to be made by private corporations in the reconstruction of areas hit by war or natural disasters but as the short film on her website suggests, disasters might also produce a fissure in social consciousness where long term political and economic actions can be rooted. I suppose it's precisely the same argument we see when relating the Lisbon earthquake and the roots of modernity. While Klein's argument continues her criticism of the proliferation of free market neoliberalism, I suppose sometimes there is the belief that the (re)ACTION needed in the wake of a disaster is too important and overwhelming to be left in the hands of democracy. (Who is that calm looking statesman rising out of the rubble, taking charge where even the angels seem perplexed? [the Clama image from class]).

http://www.naomiklein.org/main/

Anyways, there are

revolution

But the notion of cycles of history is very much inscribed within political/historical thinking. Marx famously writes in 'The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon' that history repeats itself - first time round as tragedy, second as farce. Nietzche has his 'ewige wiederkehr' or 'eternal return'. Most interesting for me is Giambattista Vico, the eighteenth-century philosopher whose thought anticipates so much of Nietzsche, Foucault, Derrida etc. He had a notion of 'ricorso': events happen first as 'corso' or 'flow', then as 'ricorso', a term that doesn't really have a proper translation. It means less 'repetition' than 'replay', with an almost legalistic sense of 'retrial' or 'appeal'.

Joyce was hugely influenced by Vico (he picked it up from Yeats, whose 'gyres' of history owe a lot to Vico's 'ricorso'); 'Finnegans Wake' is conceived completely Viconianly, with an obscure ur-event being replayed in increasingly self-conscious and self-reflective modes (as theatre, film, trial and so on). And Beckett picks up this cyclical pattern from Joyce. So in the second half of 'Waiting for Godot' Vladimir and Estragon re-enact the scene of cruelty they witnessed between Pozzo and Lucky in the first half. Or in 'Happy Days' Winnie replays the same gestures (taking stuff from her handbag) every day, while commenting on how she's replaying it - which means it's not straight repetition but a kind of historiographical archiving, or auto-archiving.

Catastrophe, Revolution, and the Narrative of History

Revolution: “C14: via Old French from Late Latin revolutio, from Latin revolvere to REVOLVE.” (Collins English Dictionary, 1986)

Revolutions ‘revolve’. The etymology suggests the (ancient? medieval?) view of history as cyclical. But after 1789 a ‘revolution’ need not be understood as a repetition of previous events, but as a radical break with the past. History became linear, not cyclical. Events could be unprecedented, and the past be broken with.

How about catastrophes? Do catastrophes reveal what has always been the case? The return of the repressed? Are they, as Blanchot says, “that which is most ancient […] that which has always long since disappeared beneath ruins” (The Writing of the Disaster, p.37)? Or do they constitute radical breaks with the past?

Was the French Revolution a political catastrophe? Did it open up to the imagination the possibility of man-made catastrophe, and the potential for human agency to radically affect change? But perhaps the French Revolution was also an ‘overturning’ that revealed no more than the ancient potential for political violence, the fall of kings, etc.

Whether catastrophes are conceptualized as ancient or as radically new may affect our understanding of the nature and narrative possibilities of (human?) history. This might also impact upon the question raised in Friday’s seminar as to whether modernity itself can be understood as a catastrophe. Perhaps modernity is catastrophic (with radical newness) because it is the age in which technology has developed such that it can destroy the earth (nuclear weaponry, global warming, etc). Or perhaps modernity is catastrophic because it is the age in which catastrophes (the ‘overturnings’ that reveal an ancient, violent underbelly) have become unsurprising: standard episodes of human history?

Shaking All Over

Gene Ray, 'Reading the Lisbon Earthquake: Adorno, Lyotard, and the Contemporary Sublime', Yale Journal of Criticism, 17 (2004): 1-18. Available to Birkbeck students through Project Muse at http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/yale_journal_of_criticism/v017/17.1ray.html

I see I have something to say about earthquakes in general in an essay of mine called The Shakes: Conditions of Tremor.

Happyclappy Catastrophe

Tom made quite a lot of reference to tragic drama in the seminar yesterday. This is appropriate, since, in uses of the word before the end of the eighteenth century, ‘catastrophe’ had a specifically literary or rhetorical meaning. It derived from ancient theories of dramatic plot, and referred specifically to the third phase of a plot, of which the first was the protasis (the setting out of the situation), the second was the epitasis (the thickening or complication of the plot), and third was the catastrophe, the resolution or dénouement. This is outlined by Samuel Gott in 1650: ‘in an ingenious Poem, which is the Creature of Fancy, the chief excellency is the Plot, and the excellency of the Plot is the strange difficulty and intricacy of the Epitasis, or troublesome state of the Business, which is afterward beyond all expectation cleared up, and resolved into an happy Catastrophe’ - Samuel Gott, An Essay of the True Happines of Man (London: for Thomas Underhill, 1650), p. 237.

The word thus came, by transference and extension, to mean the inevitable end of a process – thus ‘Apostasie is the Catastrophe of Hypocrisie’, according to William Crashaw and Thomas Pierson, in the ‘Epistle Dedicatory’ to William Perkins, A Cloud of Faithful Witnesses, Leading to the Heauenly Canaan, or, A Commentarie Upon the 11 Chapter to the Hebrewes…(London: for Leo Greene, 1607). It was also used to mean the climax of a disease.

This means that, although catastrophes were often violent, melancholy or tragic, they were not always so. Certainly, during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the word ‘catastrophe’ could frequently, as in the Gott example just quoted, signify a happy, fortunate, or just plain ridiculous outcome. Reginald Scot’s hilarious sending up of witch-mania, The Discovery of Witchcraft, describes a woman who convinced herself that she was a witch, partly because of a rumbling she thought was the devil coming for her soul. The revelation that the rumbling was the sound of a dog gnawing at a sheep is described by Scot as ‘a comicall catastrophe’ - Reginald Scot, The Discovery of Witchcraft (London: R.C. for Giles Calvert, 1651), p. 46.

2007-10-05

Dr. Benway Footage

http://realitystudio.org/multimedia/

Tom McC

Session One: 1 November 1755. The Lisbon Earthquake

The Lisbon Earthquake both destroyed countless cultural artefacts and became a major reference point for eighteenth century art. Kant’s notion of the Sublime was much indebted to it, as was Voltaire’s attack on Leibniz in Candide. This class examines the generative power of natural catastrophes from the explosion of Mount Vesuvius in the year 79 to the Asian Tsunami of 2004.

I referred to the following texts this morning:

- Umberto Eco, A Portrait of the Elder as a Young Pliny: How to Build Fame', in On Signs, edited by Marshall Blonsky (Oxford, Blackwell, 1985), pp 289-302.

- Simon Winchester, Krakatoa: The Day the World Exploded (London, Penguin, 2003)

- David Keys, Catastrophe: An Investigation into the Origins of the Modern World (London, Century, 1999)

Burroughs audio

http://cdn.libsyn.com/inkxpotter/smsd070604.m4a

Pull the cursor forwards about a quarter of the way and you get it.

Tom McC

2007-10-04

Catastrophe

(kãtæ-strõfi)

1. The change which produces the final event of a dramatic piece; the dénouement.

2. ‘A final event; a conclusion generally unhappy’ (J.); overthrow, ruin 1601.

3. An event producing a subversion of the order or system of things 1696. esp in Geol.

A sudden and violent physical change, such as an upheaval, depression, etc (See CATACYLSM, CATASTROPHISM.) 1882.

4. A sudden disaster. (Used very loosely.) 1748.